The head of a plastic bag industry group, whose full-time job consists of battling local bans on disposable grocery sacks, made a provocative observation to me about trash recently: Don't be so quick to reject waste, he warned.

"Zero waste would mean a zero economy."

Equating green with economic ruin is a familiar refrain, of course, but this claim about waste is worth a hard look. Trash really is the biggest thing Americans make, and it tends to get bigger in good times while shrinking during recession. Does that mean, as counter-intuitive as it sounds, that garbage is good? Should the old saw about waste not, want not really be waste more, get more? Should Americans just chill out and revel in the fact that we are the most wasteful people on the planet, rolling to the curb 7.1 pounds of trash a day for every man, woman and child -- a personal lifetime legacy of 102 tons of garbage each? Doesn't that just show that we're buying lots of stuff and living large -- that we should throw ourselves into a dirty love affair with trash?

Just the opposite. After immersing in the world of Garbology for the last year and a half I’ve learned some shocking truths about the high costs of our garbage. Here are some numbers to consider:

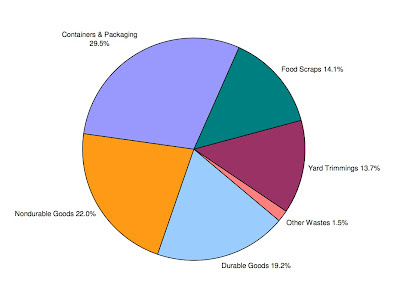

Americans make twice as much waste per person as in 1960. Most of the increase is from "instant trash' -- packaging, wraps, containers and bags, the biggest component of our garbage these days.

Garbage is our No. 1 export. Not computers, cars or planes. Our biggest export is the scrap paper and metal that China turns into products and packaging, which they sell back to us. America has turned itself into China's trash compactor.

Many American communities pay more for waste management than for parks and recreation, fire protection or school textbooks.

The average American makes 7.1 pounds of trash a day, according to the best available data (from a biannual surveys of American landfills by Columbia University and the journal BioCycle). That compares to 2.5 pounds per person in Japan.

The U.S Mail is more than half junk mail, 85 billion pieces weighing 4 million tons last year (about one out of every 100 pounds sent to the landfill). We subsidize junk mail with an artificially low postal rate and by excusing the creators of this unwanted waste product from cleaning up their own mess.

America sends 69% of its municipal solid waste to landfills. By comparison, the Netherlands and Austria landfill 1% of their trash, Sweden, 2%, Belgium and Denmark, 4%. Germany claims zero landfilling. Those countries recycle at two to three times the rate of the U.S., and make energy with the rest of the refuse. We, on the other hand, make geographic features out of our trash.

Waste is a cost, not an economic engine. Businesses understand this -- Wal-Mart has reduced its landfilling in California by 80% and ramping up recycling and reusing to the point that waste is not a profit center instead of a cost. Families know it too: Artist Bea Johnson of Marin County has presided over her family's commitment to buying unpackaged bulk goods, refusing plastic and disposable products, selecting used and refurbished items, and buying more wisely, with a focus on durability and need rather than disposability and impulse purchases. It's not enough to reuse and recycle, Johnson says. "You have to refuse!"

The Johnsons' household expenses have dropped by 40%, making college funds, a hybrid car and cool vacations possible. Their non-recycled, non-compostable trash fits in a mason jar -- for the year.

Zero waste doesn't mean zero economy. It means a different economy, with different winners. And fewer mountains of garbage.

Cross-posted at Bagmonster.com

"Zero waste would mean a zero economy."

Equating green with economic ruin is a familiar refrain, of course, but this claim about waste is worth a hard look. Trash really is the biggest thing Americans make, and it tends to get bigger in good times while shrinking during recession. Does that mean, as counter-intuitive as it sounds, that garbage is good? Should the old saw about waste not, want not really be waste more, get more? Should Americans just chill out and revel in the fact that we are the most wasteful people on the planet, rolling to the curb 7.1 pounds of trash a day for every man, woman and child -- a personal lifetime legacy of 102 tons of garbage each? Doesn't that just show that we're buying lots of stuff and living large -- that we should throw ourselves into a dirty love affair with trash?

Just the opposite. After immersing in the world of Garbology for the last year and a half I’ve learned some shocking truths about the high costs of our garbage. Here are some numbers to consider:

Americans make twice as much waste per person as in 1960. Most of the increase is from "instant trash' -- packaging, wraps, containers and bags, the biggest component of our garbage these days.

Garbage is our No. 1 export. Not computers, cars or planes. Our biggest export is the scrap paper and metal that China turns into products and packaging, which they sell back to us. America has turned itself into China's trash compactor.

Many American communities pay more for waste management than for parks and recreation, fire protection or school textbooks.

The average American makes 7.1 pounds of trash a day, according to the best available data (from a biannual surveys of American landfills by Columbia University and the journal BioCycle). That compares to 2.5 pounds per person in Japan.

The U.S Mail is more than half junk mail, 85 billion pieces weighing 4 million tons last year (about one out of every 100 pounds sent to the landfill). We subsidize junk mail with an artificially low postal rate and by excusing the creators of this unwanted waste product from cleaning up their own mess.

America sends 69% of its municipal solid waste to landfills. By comparison, the Netherlands and Austria landfill 1% of their trash, Sweden, 2%, Belgium and Denmark, 4%. Germany claims zero landfilling. Those countries recycle at two to three times the rate of the U.S., and make energy with the rest of the refuse. We, on the other hand, make geographic features out of our trash.

Waste is a cost, not an economic engine. Businesses understand this -- Wal-Mart has reduced its landfilling in California by 80% and ramping up recycling and reusing to the point that waste is not a profit center instead of a cost. Families know it too: Artist Bea Johnson of Marin County has presided over her family's commitment to buying unpackaged bulk goods, refusing plastic and disposable products, selecting used and refurbished items, and buying more wisely, with a focus on durability and need rather than disposability and impulse purchases. It's not enough to reuse and recycle, Johnson says. "You have to refuse!"

The Johnsons' household expenses have dropped by 40%, making college funds, a hybrid car and cool vacations possible. Their non-recycled, non-compostable trash fits in a mason jar -- for the year.

Zero waste doesn't mean zero economy. It means a different economy, with different winners. And fewer mountains of garbage.

Cross-posted at Bagmonster.com